The Chumash people’s connection to the Pacific Ocean dates back thousands of years. Now this ancient, unbreakable bond with the sea is on the verge of entering a new era with the impending designation of the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary, which could become official in 2024.

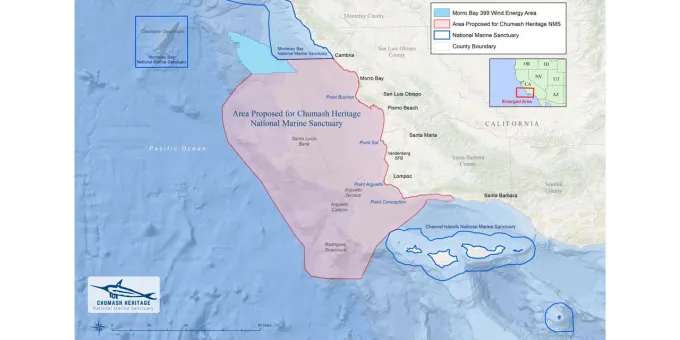

The sanctuary is a protected area that, depending on the final proposal, could encompass more than 7,500 square miles and stretch for nearly 160 miles from San Luis Obispo County to Santa Barbara County along the Central Coast. With kelp forests and nutrient-rich waters supporting huge populations of seabirds, sea otters, seals, and sea lions, as well as 13 species of whales and dolphins, the area is considered one of the world’s most biologically diverse and ecologically productive regions. Some liken the Central Coast to a marine counterpart of Africa’s Serengeti Plain.

As the first tribally nominated national marine sanctuary in the U.S., the proposed sanctuary represents an important milestone in a growing environmental and cultural movement. Indigenous peoples are seeking a greater role in the stewardship of traditional territories, while also raising public awareness of their ongoing ties to ancestral lands and waters.

The power of the sanctuary proposal lies in the incorporation of traditional ecological knowledge and a collaborative management approach between the Chumash and federal agencies.

“We know the importance of protecting this vital stretch of ocean, for our marine life, our fishing, and our cultural heritage,” says Violet Sage Walker, chairwoman of the Northern Chumash Tribal Council, which has led the sanctuary drive. “This sanctuary will put Indigenous communities in partnership with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The collective knowledge of the Central Coast’s First Peoples, as well as other local stakeholders, scientists, and policymakers, will create a strong foundation to have a thriving coast for generations to come.”

Everyone benefits from the collaboration, according to Joel R. Johnson, president and CEO of the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation. “This Indigenous-led nomination advances ocean justice and equity by protecting ancestral waters,” he has stated, “and giving everyone the opportunity to learn from the Central Coast tribes’ traditional knowledge and ways of stewarding cultural and biodiverse resources.”

An Oceangoing People

“The ocean is our life,” Walker says in a video supporting the establishment of the sanctuary. “The life of the Chumash people is intertwined with the ocean.” Before 1769, when the founding of the mission system marked the beginning of the Spanish colonization of California, an estimated 20,000 Chumash lived in villages along the coast between today’s Los Angeles County and the Central Coast. (Today, in addition to the Northern Chumash, the population includes members of the federally recognized Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians, the Barbareño Band of Chumash Indians, and the Barbareño/Ventureño Band of Mission Indians.)

The Chumash depended on the ocean and gathered abalone, both for food and as a material to craft jewelry and fishing hooks. They turned pelican bones into flutes and seal pelts into clothing. Chumash boat makers fastened together sections of planks cut from redwood trunks and sealed the wood with tar from naturally occurring seeps to build tomols. These oceangoing canoes are considered perhaps the most advanced technological achievements created by any Native American tribe (the Tongva also built plank canoes, which they called ti’ats). The tomols allowed the Chumash to venture far offshore to hunt, fish, and trade with villages on the Channel Islands.

The proposed sanctuary will protect areas with submerged Chumash sacred locations and settlements. The sanctuary’s waters are adjacent to a number of major Chumash cultural sites along the coast, including Point Concepcion due west of Gaviota State Park in Santa Barbara County. The original 2015 sanctuary nomination described Point Concepcion as “a highly revered sacred place” that the Chumash considered “a gateway for the souls of the dead to enter the heavens and bring their celestial journey to paradise.” Other significant village sites are located at Jalama Beach in Santa Barbara County, at Avila Beach, and along Morro Bay.

Decades in the Making

The dream of establishing the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary dates back more than 40 years. The late Fred Collins, Walker’s father and onetime Northern Chumash tribal council chairman, was a tireless advocate for the sanctuary and played a key role in drafting the final nomination. In a video interview, Collins spoke of the sanctuary as a project not only for today but that would benefit later generations. He used the term “thrivability,” a Chumash concept that emphasizes a balanced connection with the natural world.

“A lot of the Indigenous people around the world have given up. I still believe there’s hope,” he said. “I believe that we can together create a momentum for thrivability. It’s connecting everybody, it’s connecting everything… Thrivability is a vision that lasts for eons into the future.”

Advocates for the sanctuary believe that it could spur new educational opportunities and yield economic benefits through additional sustainable tourism and outdoor recreation. Funding for marine research could increase, and while the sanctuary proposal will prohibit oil and gas exploration and production, as well as seabed mining and acoustic testing, it won’t place limits on fishing.

What’s Next

One ongoing issue is how to establish the sanctuary while accommodating the development of the Morro Bay Wind Energy Area, a project with offshore floating wind turbines beyond sanctuary boundaries. The Northern Chumash have long envisioned that the sanctuary would start at Cambria. With Cambria as the northern boundary, the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary would create an unbroken protected area of sanctuaries along the coast extending from the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary off Mendocino County, down through the Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, and all the way to the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary off Santa Barbara and Ventura.

But to allow for subsea cables that connect the offshore wind farms to the mainland, the sanctuary proposal submitted by NOAA excluded a corridor between Cambria and south of Morro Bay to roughly Montaña de Oro State Park. That option also leaves out 30 miles of coastline that includes Morro Rock, a natural landmark of great cultural significance to both the Chumash and the Central Coast’s Salinan people. (The Salinan consider a portion of the sanctuary part of their ancestral territory and have questioned the exclusive designation of the sanctuary as Chumash, rather than acknowledging the Salinan connection to the area.)

The public comment period for the sanctuary closed on October 25 and backers hope for official sanctuary designation sometime in 2024. If the original proposal is approved, the Chumash Heritage National Marine Sanctuary would be the largest marine sanctuary off the continental United States.